On preserving knowledge

Last week, I was discussing with a colleague when I remembered a story I’d read (indexed using HN aggregator). During this conversation, I muted myself for a while and started multi-tasking while searching for the link I bet I had handy. A few minutes passed, and I was still without the hyperlink or an apparent response to my colleague’s words. During those minutes, I lost searching for the story through my bookmarks

> cat bookmarks_06_06_2023.html | grep -o 'HREF' | wc -l

2338

I mentioned to him the idea and the resemblance of the concept behind the story I was trying to remind him of, and he looked at me as a crazy person, nodding. It was different this time for me: The need for the link to probe what I was saying because the story was so well-written that my words could not make it.

After searching heaven and earth and even trying to ask the community, I decided it was clear: it was lost.

However, just by the concept of loss, it was weird to imagine a hyperlink being “lost.”

Still, how often did we lose our hard drive while kids played with Ghost during afternoons trying to install Linux from scratch on top of Windows?

But this time, it was different, I could feel it. A disk, which is a physical thing, is easier to imagine being “lost.” Still, in this case, even knowing that the web pages are hosted in another physical location within the server, it was impossible to imagine them as lost lost.

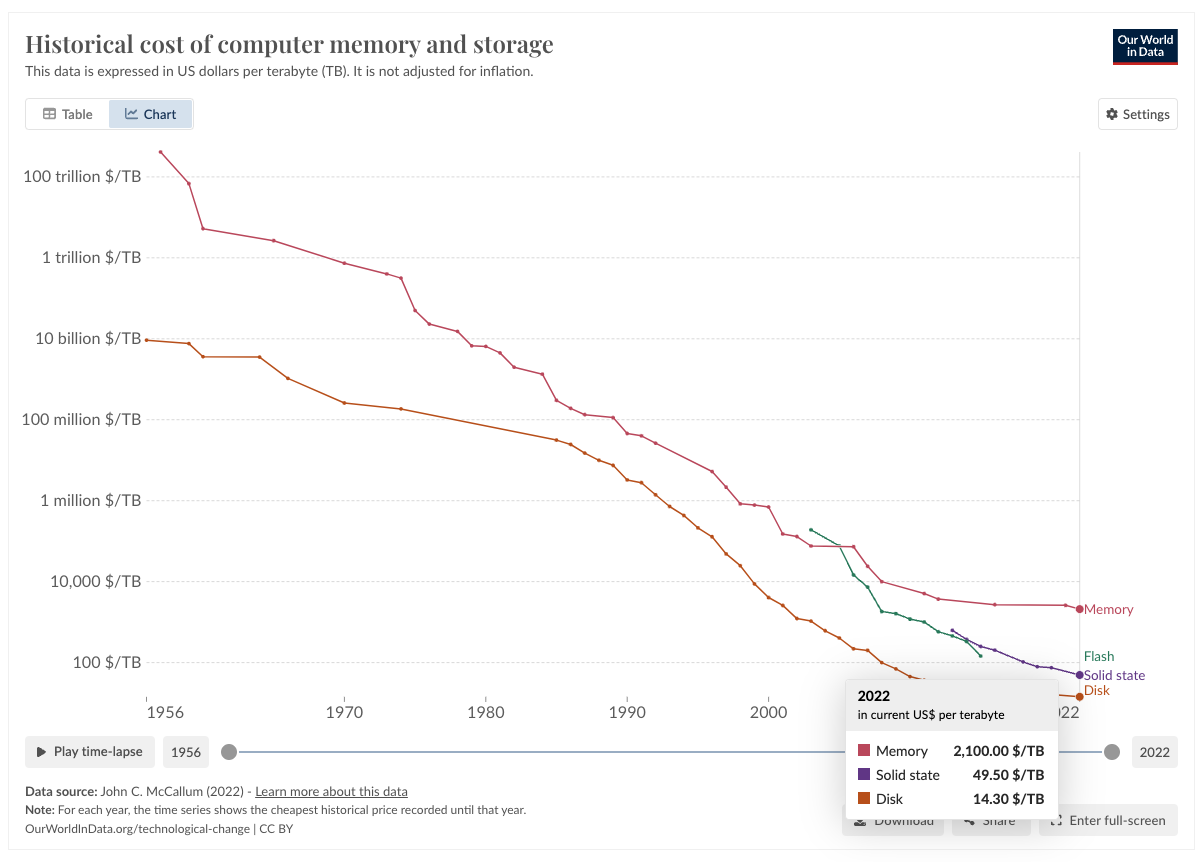

Preserving knowledge now is by far one of the biggest challenges we have as a species; not because it’s complex or expensive (storing data is practically free)

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/historical-cost-of-computer-memory-and-storage

In today’s digital world, preserving information feels like an endless game of whack-a-mole. You need to avoid cyber attacks, manage hardware maintenance, adapt to new storage technologies that might change everything, and deal with data storage issues of the weirdest kind. And this list could go on forever. It’s a full-time job, especially considering the daily avalanche of data we generate.

Every text message, photo, or tweet we send adds more bytes to an overflowing digital universe that increases daily to numbers no other human society has seen before.

You might think platforms offering “free” infinite storage, like Instagram and Pinterest, are a solution. But they are not: these platforms aren’t charities but businesses. They’ll use your data to train their algorithms or create new products. You’re paying them with your personal information. So, preserving knowledge with them is theoretically a no-go since it won’t be yours as soon you drop it into their folders.

Are you trying to remember that blog post you read ten years ago in a discussion? Good luck finding it now, if not in your bookmarks (even if there is a challenge).

Web tools have changed, servers have gone offline, and new platforms have risen. All of this while you have been searching for this article. It’s like trying to find your way back to a childhood home that no longer exists.

The Internet has become so big and noisy that being findable is challenging. You can index your webpage to any aggregator but without the right keywords. Keeping your knowledge close using books is an old but good way to see how much knowledge you have at hand, but it needs to be more scalable to the scale we are used to having regarding Internet content.

Self-hosting might also be a solution, although, as discussed below, the burden of maintaining everything by yourself is a job on its own

It’s like shouting into a void. No one will hear you, and the irony behind it is that you’re not lost but still unfindable.

What’s the point of not being lost but still waiting for someone to be able to find you?

It may be time to redirect our efforts: let’s create a tool to preserve knowledge, but please use something other than LLM for this! (they will compress it.)

After all, much of what we’re looking for online has the danger of becoming nothing more than digital tears in the rain.

Even this post.